Rising From the Ashes: A Conversation with Pete Hoskins, Retired President of Philadelphia Zoo

- Grayson Ponti

- Feb 28, 2018

- 11 min read

In 1993, Pete Hoskins became President of Philadelphia Zoo largely in respect to his late friend and mentor Bill Donaldson. He would spend the next thirteen years at the helm leading the zoo as it grieved the tragic loss of the zoo's primates during a fire and celebrated the opening of PECO Primate Preserve and the award-winning Big Cat Falls. Here is his story.

@ Pete Hoskins

Prior to working in zoos, Pete Hoskins was Director of Philadelphia’s Fairmount Park system and commissioner of the streets department. His connection to Philadelphia Zoo began with his friendship to Bill Donaldson, the zoo’s president from 1979 to 1991. “Bill Donaldson was the former City Manager in Cincinnati and Scottsdale,” Hoskins recalled. “I always wanted to be city manager so I made it a point to spend a fair amount of time with Bill. Bill was a maverick wherever he was. When he became the zoo director, it was his calling. In the 60s and 70s, the city of Philadelphia was in a decline and was pulling its support from the zoo. Bill was instrumental in beginning the Philadelphia Zoo back on the map again. He was very good at marketing and began to promote the zoo very strongly.” Sadly, Donaldson got cancer and passed away in 1991.

@ Philadelphia Zoo

A search began to replace Donaldson but Hoskins initially didn’t apply. However, halfway through the year, he was asked to consider it. “I thought succeeding Bill Donaldson would be a natural way to bring my city management skills to the zoo,” Hoskins remarked. “I didn’t know the world of zoos very well but I knew the city and the budgets of the zoo very well. After twenty years of working with the city, I thought I could do it.” In 1993, Hoskins became President of the Philadelphia Zoo.

@ Philadelphia Zoo

@ Philadelphia Zoo

While Donaldson had succeeded at improving marketing efforts at the zoo, he had limited success improving the zoo’s exhibits and facilities. “They still hadn’t been very successful in raising money for modernization,” Hoskins stated. “I felt I was able to build on his legacy and make the zoo relevant in the city and modernize it physically.” A number of the zoo’s exhibits were outdated. “It was America’s first zoo but also America’s oldest zoo,” Hoskins commented. “Much of the zoo was of the old era and wearing down.”

@ Philadelphia Zoo

Hoskins and his team soon embarked on a master plan process to update the facility. “The question as what do we do first, second and third and looked at the zoo over the next 15-20 years,” he explained. “The master plan process was very important and we worked with other professionals, notably CLR Design. We developed the financially daunting task of bringing the zoo into the future. Virtually every exhibit in the zoo had seen its day so what order should things happen? An education center was seen as an idea to start that process. The original idea was to have it in the courtyard of the old lion house, which seemed like a half measure. We then came up with some new ideas for an education center that would be an exciting exhibit, serve the needs of education at the zoo and work with schools. It would be a good way to honor Bill’s legacy.”

@ Philadelphia Zoo

One of the challenges the master plan team had was limited space. “With Philadelphia Zoo being 42 acres, we had to make wise decisions about what species you could present and tell the stories that needed to be told,” Hoskins remarked. “When I arrived, chimpanzees were left behind in the Rare Animal House- a terrible exhibit that never did justice for chimps. They required a lot of space we didn’t have so we decided that we shouldn’t have chimps if we couldn’t do them well. The chimps were taken to Saint Louis and Honolulu where they could be in places where they could thrive as animals and be presented modernly.”

@ Philadelphia Zoo

@ Philadelphia Zoo

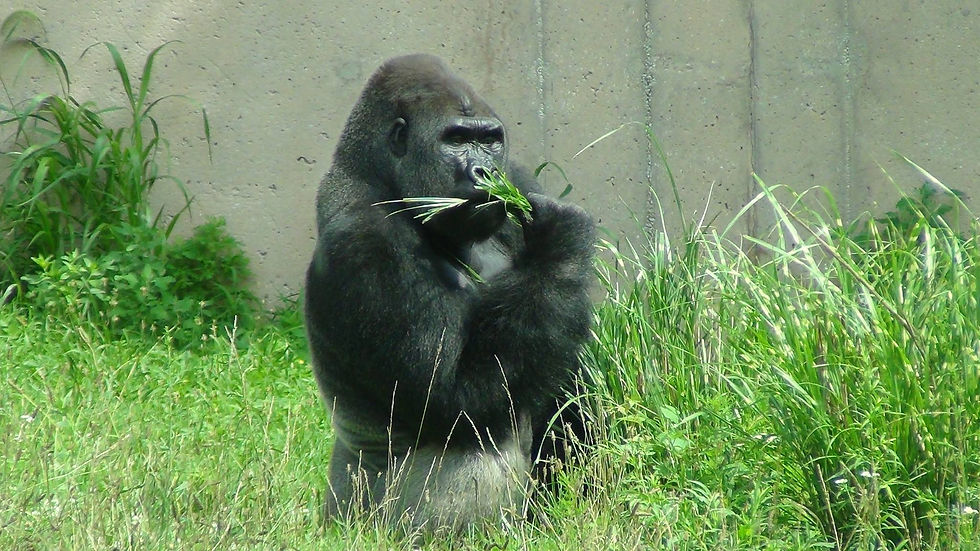

However, the zoo’s plans at implementing the master plan turned upside down when tragedy struck Christmas Eve 1995. A heating cable caused a fire to erupt in the Primate House, destroying the building and killing all 23 gorillas, orangutans, gibbons and lemurs inside. It was “World of Primates was the newest exhibit we had,” Pete Hoskins remembered. “No one could have possibly expected it would be the place for such a disaster. We decided early on we would use this tragedy to create one of the world’s finest primate facilities. When that happened, a primate center became the master plan priority. We had an exhibit that was completely destroyed and had to be replaced. With that tragedy, we had to build a path to triumph over tragedy.”

@ Philadelphia Zoo

@ Philadelphia Zoo

It was Hoskins’ responsibility to move the zoo forward and help the community around it cope with the loss. “That was a long path as just getting past that terrible moment was very emotionally difficult for the staff and the people who loved the zoo,” he elaborated. “They all had to go through their own stages of grief and we had to work with that. There was a lot of anger over the loss. Those of us close to the fire went through our grief quite rapidly as we lived with it 24/7 for months. We used that time to rethink how we would move to the highest standard in honor of those lost primates.”

@ Philadelphia Zoo

@ Philadelphia Zoo

Philadelphia Zoo remained closed until New Years to build a memorial for the lost primates. “We exhibited very large photographs of each of the [deceased] animals and had keepers write their memories of those individuals,” Pete Hoskins commented. “We allowed people to come in for free in January to grieve and remember the lost animals. We had tens of thousands of people come. We had children donate the contents of their piggybanks and people calling asking how they could help. Allowing people to be a part of it helped us set the stage of surviving the grief."

@ Philadelphia Zoo

@ Philadelphia Zoo

Not only was the grief shared with the community of Philadelphia but also the broader zoo community. “About a month and a half after the fire, we had the annual zoo director’s retreat,” Hoskins remembered. “About 100 or so of my colleagues gave me whatever time was needed to tell the story of what happened and what we were doing. It was probably one of the most traumatic and touching moments of my life standing in front of them and telling that story. Each of them could clearly see ‘For the grace of god. This could be me!’ I was able to take them to where they were. We were all sharing this experience together. Fortunately, almost none of them would ever suffer something like that. It was a learning experience for them as it was for me.”

@ Philadelphia Zoo

The Zoo set out to build PECO Primate Preserve, which opened in 1999. It used the resources that would have been used to build the education center. “We were in a cultural transformation at the zoo and were developing our own organization around building modern facilities using an interdisciplinary team,” Hoskins remarked. “We applied those lessons to the new primate center and we had some of the finest minds in the zoo world brought to bear in the design. A key team leader was Andy Baker, who was primate curator at the time and COO of the zoo now. We also had the head of education and conservation, the keepers and director of building management on that team. They were brought together with the design team to come up with what we thought would be the best of its kind.”

@ Philadelphia Zoo

@ Philadelphia Zoo

The concept of PECO Primate Preserve was an abandoned lumber factory turned into a sanctuary for primates such as gorillas, orangutans, gibbons and lemurs. “Part of that concept was to help people understand how animals in the wild are endangered and how we can change the manmade circumstance that creates this endangerment to save them,” Hoskins explained. “We developed a setting that people could relate to and that would let them appreciate why these primates are endangered. What can we do about it? What are scientists doing to help us understand what we can do to save them?”

@ Grayson Ponti

@ Philadelphia Zoo

Steps were taken to improve the new primate exhibit from the old one in terms of animal welfare. “We spent a fair amount of time learning from the keepers what we needed to do to make the facility work better for the primates," Hoskins stated. “For example, in Primate Reserve, there’s an enormous amount of space below for the keepers to use to do what they need to do. It was designed very much in keeping with the needs of both animals and people. We also tied the exhibit to specific projects in Africa and Asia and the story of how we replaced the animals who were lost. [We talked about how] zoos in America operate as a common collection and work together to maintain family groups of animals. We had to work closely with zoos around the country to determine what animals could be brought together to create a family group and helped people understand primates are in zoos not just to be exhibited but to be ambassadors for the wild.”

@ Philadelphia Zoo

Another major task for Pete Hoskins during his tenure was to unite Philadelphia Zoo’s staff. “When I got there, there was a lot of division between the education department and animal care staff, union and nonunion [and so forth,]” he recalled. “The most important thing was to have everyone appreciate the importance of the role of every one of those people. Everyone has a job to support the animals and public we serve. The more people could appreciate their role, support others and see how what they did affected others, the better. The design process was so important as it brought together virtually every department and they could feel participated. By Big Cat Falls, I felt we were really kind of singing in harmony as a staff.”

@ Philadelphia Zoo

This also involved elevating the professionalism of the zoo’s staff. “People say a zoo is a place of disorder but the trust is you can’t run a zoo without especially orderly procedures and disciplines,” Hoskins commented.

@ Philadelphia Zoo

At the time, the Philadelphia Zoo, like its international sister zoos, grew its investment in conservation and education. “From the very beginning, I saw education and conservation as the essential reason for our existence,” Pete Hoskins elaborated. “A zoo isn’t a place just to show off animals but to tell an important story. You have to do it in a way that’s compelling and fun but has a clear and compelling mission. If you’re going to raise millions of dollars, you have to have a strong purpose. I focused a lot on that clear and compelling mission so we could get a lot of people behind supporting it.”

@ Philadelphia Zoo

“Insitu conservation was a growing field when I was at the zoo,” Hoskins remembered. “My staff and I were involved in several international committees funding projects in several countries. We were involved in projects that would connect what we were doing at the zoo to on the ground projects in the field. We’d feature these projects in our exhibits. We were part of the World Association of Zoos and Aquariums’ worldwide effort to connect conservation to zoos.”

@ Philadelphia Zoo

@ Philadelphia Zoo

After PECO Primate Reserve, the Philadelphia Zoo began plans to replace the old lion house with a state-of-the-art facility for big cats and to reimagine the bird house into a modern facility as well as completing smaller projects like modernizing the Rare Animal House and adding a lorikeet exhibit. Another one of the zoo’s priorities was a new children’s zoo. “Andy and I had an a-ha moment where we thought why don’t we move the children’s zoo to the Elephant House and turn this big barn into a great children’s zoo,” Pete Hoskins remarked. The question was what to do about the elephants. “We thought about featuring Africa to have space for animals move around,” Hoskins continued. “Andy Baker initially had experimented with free-ranging marmosets and had them go out with collars and come back each night. We thought about elephants and letting them walk a fair distance every day.”

@ Philadelphia Zoo

“Coincidentally, I had attended a national meeting for all zoos that had elephants with the national imperative to create breeding herds of elephants,” Hoskins continued. “We needed fewer zoos with more elephants. We decided we would make that attempt and declare we would commit to having elephants in a new facility in two years. Over the course of the next year, we found we just could not raise enough money fast enough. We sadly had to abandon the idea of having elephants at Philadelphia Zoo. We had to make a very conscious decision, which meant the elephants would have to move in the best interests of the animals.” In 2006, the Philadelphia Zoo began the process of moving its elephants to other homes.

@ Philadelphia Zoo

Another decision that had to be made was to find revenue-boosting attractions that replaced the disbanded monorail. “The monorail really got in the way of the exhibits themselves,” Hoskins recalled. “It took up space, disturbed exhibits and really wasn’t a great zoo experience. We replaced it with experiences that were equally fun but not in the way of the animal experience. We brought the zoo balloon to the edge of the zoo and swan boats on the lake. People want to have fun when they go to the zoo but not in a way that doesn’t take away from valuable space and the mission. It made you smile when you looked up at it but it didn’t detract from the zoo. The monorail detracted from the zoo.”

@ Philadelphia Zoo

In 2006, the Philadelphia Zoo opened the award-winning Big Cat Falls. It featured Amur tigers, lions, jaguars, cougars, Amur leopards and snow leopards in rotational habitats. “We wanted to feature the big cats of the world and show their similarities as carnivores wherever they live,” Pete Hoskins stated. “They live in different environments but have the same niche. Andy was really the brains behind having the big cats not limited to their own habitat but able to move around from one exhibit to another through overpasses and tunnels. That was where we first implemented the idea of moving animals on a large scale.” The overpasses in Big Cat Falls helped inspire Zoo360, a series of overhead trailed implemented at the zoo in the future allowing a wide variety of animals to walk above the guests and explore other parts of the zoo.”

@ Philadelphia Zoo

@ Philadelphia Zoo

A major obstacle to the construction of Big Cat Falls was working around the old lion house. “The old Lion House was like an old jail but the structure was very hard to get rid of,” Hoskins explained. “We tried to work around this very solid shell of a building and build out. The courtyard became an important place to create new space. Rather than using the old cages, we built out into the courtyard and took it out to the path. We gained an enormous amount of animal space without losing circulation for people.”

@ Philadelphia Zoo

@ Philadelphia Zoo

Instead of viewing the cats across concrete moats, guests could now get nose to nose with them through glass windows. Additionally, the animal habitats were now naturalistic and gave them opportunities to exhibit natural behaviors. “Allowing the cats to move from space to space gave them multiple experiences,” Hoskins added. “They could get the sights and smells of places they otherwise couldn’t get.”

@ Grayson Ponti

@ Philadelphia Zoo

In 2006, Pete Hoskins retired from Philadelphia Zoo. He has spent the last eight years of his career working in Philadelphia’s Laurel Hill and West Laurel Hill Cemeteries. “I had one more gig left in me,” he commented. “I’ was blessed with a varied career in interesting projects.” Still, the zoo retained a special place in his heart. “What is unique about Philadelphia Zoo is you don’t need to be the biggest to tell compelling stories about animals in the wild,” Hoskins reflected. “[The size] makes you made wise choices of what stories to tell. The zoo has done especially well at focusing on which stories to tell and which animals to exhibit.” Hoskins mentioned he was very pleased with the progress of his successor, Vik Dewan.

@ Philadelphia Zoo

@ Philadelphia Zoo

“Competing with other forms of entertainment is a challenge,” Hoskins elaborated. “Zoos need to roll with the technology that’s there and use it to tell the story even more powerfully than before. Instead of denying technology, we need to find new ways to apply it so people can have experiences with real animals when they’re there and find new ways to enjoy them when they’re not there.”

@ Philadelphia Zoo

“Rebounding from the tragedy of the fire as strongly as we did is something I’m proud of,” Pete Hoskins concluded. “We took that really tragic moment to make the zoo better. I was there from the earliest moment to the end. I feel really proud of the dedicated zoo professionals who helped make that possible and it took a very special group of people to get there.”

@ Petre Hoskins

Comments